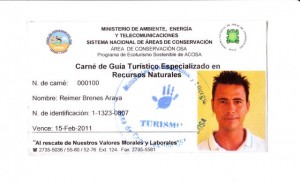

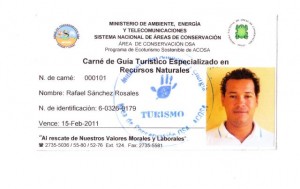

Through continuous trainings Bahia Aventuras guides have earned certifications from the Costa Rica National Area of Conservation System known as SINAC. Although finishing the courses is a great achievement, the Bahia Aventuras team continues to increase their knowledge and skills by participating in different courses and trainings. One course that the guides are currently participating in is offered by UNED. The course is composed of 7 modules such as local geography, natural history, tourist legislation, first aid and tourism control and will last approximately 3 months. Team Bahia Aventuras is always looking for opportunities to learn more in order to continue providing the most responsible and best service in the Uvita-Bahia and Osa area.

In the following months the main road to the

In the following months the main road to the  How did the olive ridley get its name?

How did the olive ridley get its name?